Few figures in literature and film have gripped the human imagination as powerfully as Dracula. Emerging from the shadows of Eastern European folklore and immortalized by Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula has become a symbol that transcends centuries, embodying not only the fear of death and the supernatural but also the evolving anxieties of modern society. The story of Dracula is not merely about one vampire—it is about how an idea rooted in medieval legend grew into one of the most enduring archetypes of gothic horror and popular culture.

The Historical Origins of Dracula

At the root of Dracula’s legend lies the historical figure Vlad III of Wallachia (Vlad the Impaler), a 15th-century prince whose brutality earned him a place in both fear and folklore. Known for impaling his enemies on stakes and defending his homeland against Ottoman invasions, Vlad’s cruel reputation gave birth to tales that blurred fact and legend. In Romanian folklore, he became both a national hero and a figure of terror.

Overlaying Vlad’s history is the deeper mythology of vampires in Eastern Europe. For centuries, Slavic and Balkan traditions spoke of strigoi—restless spirits or revenants that fed on the living. These myths arose in agrarian societies that feared unexplained deaths, plagues, and the uncanny persistence of the dead. Villagers exhumed bodies, staking them or burning them when corpses showed signs of “feeding” (bloated bodies, blood at the mouth).

It was this fertile ground of myth, folklore, and historical brutality that Bram Stoker drew upon when crafting his immortal Count. Stoker never visited Transylvania but carefully researched travelogues, folklore collections, and Eastern European legends to weave a narrative that merged folklore with the gothic tradition of writers like Mary Shelley and Edgar Allan Poe.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula and the Gothic Tradition

When “Dracula” was published in 1897, it immediately entered the canon of gothic literature. Written in epistolary form through diaries, letters, and telegrams, the novel transported Victorian readers into a story that felt both exotic and terrifyingly close to home. The Count’s castle loomed in distant Transylvania, but his threat stretched across seas into the heart of London.

Stoker’s Dracula was more than a monster: he embodied the Victorian anxieties of the time. Themes of sexual repression, fear of immigration, disease, and the collapse of rational order all converge in the Count’s shadow. The vampire was aristocratic yet parasitic, foreign yet insinuating himself into the British Empire. Stoker’s genius was to blend mythological horror with psychological and social dread, creating a story that resonated on multiple levels.

Dracula in Early Film and the Birth of Horror Cinema

With the rise of film in the early 20th century, Dracula leapt from the page onto the screen. The unauthorized German expressionist masterpiece Nosferatu (1922) reimagined Stoker’s Count as Count Orlok—a skeletal, rat-like figure of plague and decay. Though Stoker’s widow sued for copyright infringement, Nosferatu survived as one of the most haunting silent films ever made, defining the visual grammar of vampire cinema.

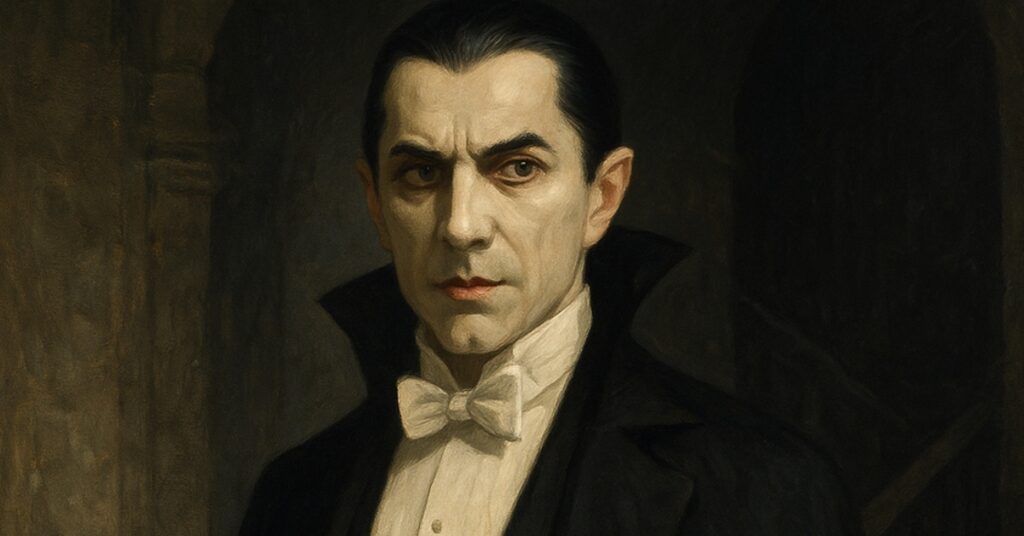

In 1931, Universal Pictures’ “Dracula”, starring Bela Lugosi, established the Count’s most iconic image. Lugosi’s Hungarian accent, piercing gaze, and aristocratic bearing created the archetype of the vampire lord in a black cape—a look still synonymous with Dracula today. The film solidified horror as a genre in Hollywood and brought Dracula into the golden age of cinema.

Dracula Through the Decades: Adaptation and Reinvention

From the mid-20th century onwards, Dracula became a canvas upon which filmmakers and writers projected new cultural anxieties.

- Hammer Horror Films (1950s–1970s): With Christopher Lee as Dracula, Hammer Studios brought gothic sensuality and blood-soaked violence to the role. Lee’s tall, menacing presence revived the Count for a post-war generation, embedding him in technicolor nightmares.

- Dracula in the 1970s–1980s: The character expanded beyond horror, appearing in comedies (Love at First Bite), animations, and even as a satirical figure. Yet darker reimaginings persisted, linking Dracula to themes of plague (during the AIDS crisis, vampire metaphors re-emerged strongly).

- Francis Ford Coppola’s “Bram Stoker’s Dracula” (1992): A lavish gothic romance starring Gary Oldman, this adaptation returned to Stoker’s text while exploring themes of love, immortality, and tragedy. Coppola’s film emphasized Dracula as both predator and tragic hero, cementing his dual role as monster and romantic antihero.

Dracula in Contemporary Culture

Dracula has never vanished from cultural consciousness. His shadow lingers in literature, television, video games, and streaming platforms. Modern interpretations include:

- “Castlevania” (video game and Netflix series), reimagining Dracula as both villain and sympathetic antihero.

- “Hotel Transylvania” (animated films), which turn Dracula into a comedic, family-friendly figure.

- Netflix’s “Dracula” (2020) by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, which modernized the Count while maintaining gothic roots.

- Countless novels, from Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles to postmodern works, which borrow heavily from Dracula’s mythos.

What makes Dracula unique is his adaptability. He can be terrifying, tragic, erotic, or even humorous, depending on the cultural moment. His archetype survives because he speaks to eternal human fears: the fear of death, the seduction of forbidden desire, and the haunting idea that evil can appear civilized and beautiful.

Dracula’s Symbolism and Enduring Power

Why does Dracula endure when so many other monsters fade? The answer lies in his symbolic weight. Dracula represents:

- The Outsider: A foreigner invading established societies.

- The Predator: Feeding on the life force of others, mirroring anxieties about exploitation.

- The Immortal: Defying death but cursed to live without peace.

- The Forbidden: Embodying sexual, moral, and social taboos.

In every era, Dracula morphs to embody contemporary anxieties. In Victorian times, he was the immigrant threat. In the Cold War, he was Eastern Europe’s shadow. In the age of pandemics, he became a metaphor for contagion. And in today’s fractured world, Dracula reappears as a symbol of toxic power, hidden corruption, and the dangerous allure of the eternal.

Conclusion: Dracula as a Mirror of Humanity

From folklore and Vlad the Impaler to Bram Stoker’s masterpiece and the hundreds of cultural adaptations that followed, Dracula has proven to be more than a character—he is a mirror of human fears and desires. Across centuries, Dracula has remained relevant because he evolves with us. Whether he emerges as a cloaked nobleman in black-and-white cinema, a tragic lover in gothic romance, or even a comic caricature, he is always present in our imagination.

Dracula is not just a vampire. He is a cultural archetype of horror itself, a reminder that what we fear most often reveals more about us than about the monsters we invent.