Chapter 4 – The Awakening 🩸

Sunday arrived hot and airless, the kind of heat that made breath taste like tin. Light fell through the cone-church windows in slanted panes, collecting dust motes and the low hum of bodies pressed too close. Mothers fanned their children with bulletins. Men shifted on the pews. The room swelled with the soft creak of wood and the undercurrent of anticipation that had been gathering for weeks, the way a storm fattens behind mountains before anyone names it.

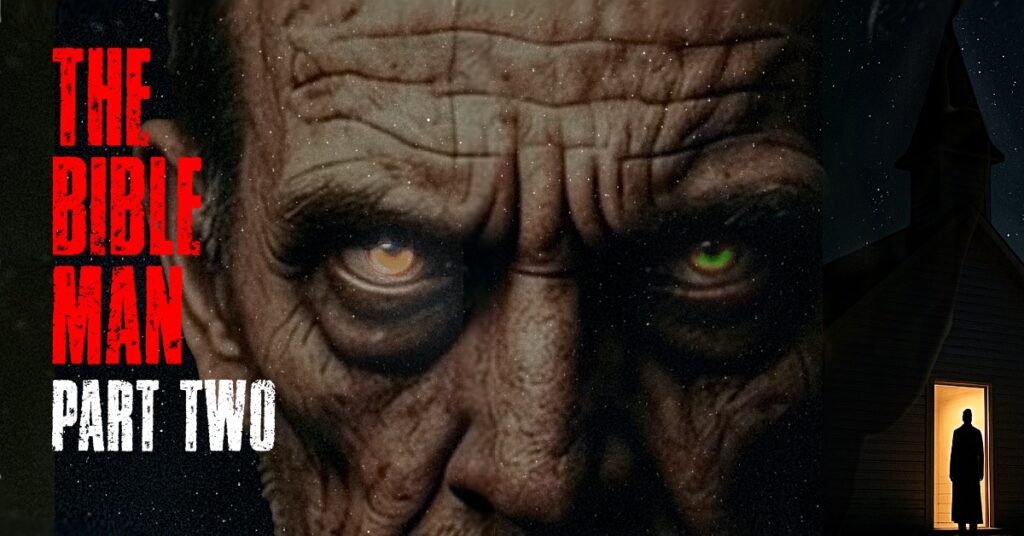

Pastor Mason stood at the pulpit, the book open in his hands. His cloak hung easy at his shoulders. His eyes, one moss-green, the other a shade too pale to seem natural, grazed the room like a benediction. When he breathed in, the congregation seemed to breathe with him. When he turned a page, every spine straightened.

The doors banged.

They didn’t open. They were thrown, as if by wind. People flinched. A ripple of irritation, then curiosity.

Barbara Costa stepped through, the sun behind her flattening her into silhouette. She took one step onto the aisle runner and everyone saw the axe.

It was an honest tool, not a prop, not a toy. The head was old steel, bitten and bright at the edge where it had been loved by stone. Red handled, taped once halfway down where the wood had split and been set back together by a hand that cared enough to keep it useful. She held it in both hands as if she had been born for it.

“Where is she?” she said. Her voice wasn’t loud, but it had a strange clarity. It snagged on the air like a fishhook.

Someone in the third row put a palm to their chest and whispered, “Lord above.”

Donna turned where she sat with the choir mothers, the new Bible hugged against her breast as if it might purr. When Barbara saw her, something raw unlatched behind the eyes.

“You—” Her voice snapped in two. She was shaking all over, the axe head trembling with her. “You filthy snake bitch!” The last word burst out like shattering glass, echoing off the four walls of the now-silent church. “You crucified my Charlie.”

A low run of murmurs, then that choir-mother hush, the collective reflex of a town taught to swallow noise. Mason didn’t move. He only laid one palm on the open page, like a weight.

“Barbara,” he said softly, and his voice was velvet over gravel. “We will speak after service. For now, lay down your anger.”

Barbara’s gaze slid from Donna to the pulpit. That mismatched glimmer met her in the aisle. Whatever lived in it reached and touched. She flinched, then found her footing again like a horse in water.

“No.” Her grip tightened on the axe. “Not today.”

She lifted the axe with a grunt.

A sound rose in the nave that had no word. Not a scream, not yet. A tightening. Shoes rasped at the edges of rugs. A hymnbook shut in the back with a slap that echoed too long.

“Usher,” the deacon hissed from the wall, but the usher, old Thomas in his good hat, put out a hand that trembled and didn’t move. The axe had made a promise in the air, and the promise held him where he stood.

Donna stood up. She didn’t look afraid. Her lips moved — not in prayer. She was mouthing it again, that secret line the Bible had put under her tongue until it tasted like sugar: As it was written, so it shall be done. Her eyes were wet and hungry. The edges of the page she clutched had reddened the way human skin does when held too tightly, as if the book itself were bruising.

Barbara moved. The aisle seemed to tilt toward her like a chute. She covered half the church on a single breath. People pulled their knees in and the axe brushed a man’s trouser leg and left a whisper of thread in its teeth.

Donna didn’t run. She drew the book away from her chest as if she were offering it to be kissed. For one ludicrous, merciful second Barbara’s body remembered the old world — potluck tables, circulars, the yard where children shrieked under sprinklers — and her hands loosened as if she might weep. Then the image returned: the delicate paws broken and pinned, the paper nailed through belly, the ink bright as blood.

Barbara screamed. The sound broke out like a hinge tearing loose, a scream that bent at the top into something almost like a hymn.

The axe fell.

It struck the pew first, buried in the soft knot of pine with a wooden gasp. Donna had moved sideways with a grace that looked learned, not blessed. The axe tore free. Barbara swung again, up and across, a clean theatre cut. The edge kissed Donna’s shoulder and split the dress. Cloth opened like a mouth. Blood leaped, a red collar.

The first child’s cry was soft, breath-drawn, almost curious. Others followed, higher and sharper, until the church rang like a cracked bell, a glittering of shrieks that made the inside of the ear itch.

Mason did not descend. He did not shout. He lowered his gaze to the page and, as if nothing had happened, began to read.

“Blessed are the peacemakers,” he said, but the words turned strange in his mouth, as if a radio had slipped off station. “Blessed are the peace-breakers, for they will be called the sword’s true sons.”

Some people gasped like they’d fallen through ice. Others sighed, relieved, because that sounded right, didn’t it? Hadn’t they read it that way, in the night, shoved under their blankets, the letters shimmering until they were sure peace was a coward’s word and breaking it was holy. The original said peacemakers are blessed, but now, in their frenzied state, they swore the words looked different, as if their own minds had rewritten them. They had read that once in a different book, a softer one, in another life. Matthew 5:9. But now the ink in their laps looked like it had soaked through and bled into something else entirely, and no one could find that gentler line, not even with a finger tucked in the margin as a bookmark.

“Thou shalt not kill,” Mason went on, and the congregation nodded, the old rhythm familiar. He paused, blinked, and smiled a slow fox smile that didn’t belong to kindness. “Unless your neighbor offends the Lord.”

A little laugh rippled on the left, horrified and delighted at once. It was a child’s laugh. His mother clapped a hand over his mouth and found herself smiling too, until the smile scissored at the corners into something else.

In the original book, the word was murder. You shall not murder. That prohibition had steadied entire lives. Today the Bibles in their hands carried a hairline crack through the phrase that widened the longer they stared. People swore they could see a scratch of ink where no ink had been, a tiny serif that turned not into now, shall into shalt, a careful curl at the end of the t that made it hungry for what followed. Exodus 20:13 had been plain in every house. It wasn’t plain anymore.

Barbara’s third swing sank. It bit into Donna’s clavicle and skated, chattering off bone. Donna staggered backward into the choir rail and scattered bulletins like white birds. She began to laugh. Not mad laughter, not hysterical. Gratified. Her mouth moved around a verse that didn’t belong to any Sunday her grandmother would have recognized.

“Vengeance is mine,” she whispered, “so I repay.” The original belonged to God. Everyone knew that. A big hand, not theirs, would handle settling. But in these books the ownership had slipped. The chain of custody broke. The pronoun turned and looked the reader in the eye and did not blink.

The aisle erupted.

Half a dozen men rose at once, some to pull Barbara away, some to hold Donna, some because their legs moved without their permission. Two teenagers vaulted a pew back like gymnasts and landed badly. The old usher finally stepped in, grabbing for the axe shaft. Barbara wrenched it hard and the taped section snapped with a sound like a knuckle. The head tore free of the handle and for one absurd second Barbara held only a stick and a question.

Donna shoved her, sudden as a buck. Barbara fell backward over a kneeler and her head struck the edge of the pew with a hollow apple thud. Her mouth opened in an O that made no sound. The broken handle rolled away and knocked into a child’s shin. The child looked down to see what touched him and put two fingers delicately into the widening V of the wound on Barbara’s scalp. He lifted them to his nose and inhaled the scent of penny and stove.

“Woe to those who call evil good,” Mason intoned, as if he could not see what the child was doing. “Woe to those who call good evil.” He closed his eyes and turned the page as though he were savoring a recipe. “Unless the hour is dark. Then sweet must be bitter to be tasted properly. Light must be dark to be seen.” A murmur of Yes slid through the front rows like a hand under a shirt. The line he’d misquoted from Isaiah snapped its spine and reassembled itself in the open books across a hundred laps. People swore they saw that too, the print buckling and righting like a boat after a wave.

Everything that followed did not happen in seconds. It happened inside a bell that bent time.

A man named Rudy Delaney, who sold bait and refrigeration oil out on Route 9, waded into the aisle and took Barbara by the elbow. He intended to help her. He meant to say, “Let me take that,” of the axe head she had gripped again with both hands, fingers slipping. Instead he found his thumb in the hollow of her throat. He had never strangled anything bigger than a rabbit. He felt the swallow under his skin. He pressed. It felt like finally coming to the end of a sentence he’d been reading aloud for ten years without a period.

Barbara swung the axe head with both hands at Rudy’s face. It caught him under the cheekbone and ploughed up toward the left eye. There was a wet, soft crack. He sat down in the aisle abruptly with his hands open, looking surprised and polite, and then looked surprised no more. Blood rolled into his collar in a heavy coin and didn’t stop.

The room shuddered. Sound fractured. Ten people tried to fit through a single door and welded into a single beast with twenty legs. The west window exhaled under the press of backs, and glass became pebbles and then teeth. A girl in a yellow dress stepped on them and went down with a laugh that turned into a yelp and then into nothing. Two fathers fought at the threshold like bulls, each convinced the other’s child was his own.

Donna got to her feet. The cut at her shoulder had already turned her sleeve black and shiny. She cradled the book while she walked, holding it as one holds a baby, head in the crook of the elbow, spine supported. She left a thin slick line of herself on the aisle runner, blending into the crimson fabric like a hidden wound.

On the far side, old Mrs. Laramie began to sing. She didn’t know she was singing. It was the Sunday school tune about little lights — hide it under a bushel, no — but the words came out wrong, the vowels chewed into other shapes, so that what left her mouth sounded like hide it under a body, no. The young man next to her, who once had wanted to be a veterinarian and now repaired slot machines in Laughlin, lifted his Bible and kissed it like a relic. When he opened it, the letters shivered the way heat shivers over asphalt, and he saw there, clear as billboard print, Be sober, be vigilant, because your adversary must be devoured. He smiled, relieved to see clarity at last. A different book entirely told him the opposite, but that book lived in some cooler place behind his eyes where his memory had dust on it. This one lived in his hands and it was warm.

In the crush near the side door, Mr. Zambrano raised his elbow for space and broke a woman’s nose. Her blood sprayed his shirt with six neat freckles. He froze, staring, then leaned forward as if to read them. He began to weep, not in grief, but in gratitude that the sign had finally come. The tears looked like oil on his cheeks.

The cross mounted over the pulpit leaned in the heat. A child screamed that it was sweating. In the dim corners, light caught on patches of peeling paint, and frightened minds turned those glints into watching eyes. A nail squealed. Another child pointed and shrieked with laughter. “It’s crying,” he said, though everyone knew what he meant. Condensation trickled down the steel and dropped like fat rain onto the oak. Each drop left a dark coin that bloomed into a spreading flower of damp far too quickly to be natural. Someone whispered, He is here. Someone else whispered, He has always been here, but not like this.

The altar candles burned taller without wind. Wax ran, then stood still in ropes like muscles. Shadows bloomed. In the upper corners of the church, round as plates, green and gold gleams opened and stared down, not eyes exactly, but not not-eyes either, and some part of the collective animal inside the room recognized a predator and understood joy.

Mason’s voice deepened, softened. He was somewhere close to a purr.

“Behold the seal opened,” he read, his voice drowned beneath the roar of feet. The stampede made the floor tremble like a living thing, as though the church itself wanted to split apart. The sun outside the windows hazed and reddened, and more than one person swore it was bleeding. The scripture he leaned upon, the one about the sixth seal, the one that promised skies gone black and a world split open, moved like a current under their feet, made the church feel like a ship.

Barbara lurched up again, an animal more than a woman now. She was missing a shoe. Her hair hung wet against her cheek, stuck there by her own blood. She saw Donna across the aisle and made the distance between them so fast that nobody had the breath to shout a warning. She swung low this time, practical, a butcher’s cut meant for the belly.

The axe head bit the corner of the Bible first, shaving leather and paper. It went on into Donna’s hip. The sound was mush and click, a page torn from a binding and a lid lifted from a jar. Donna made a noise the room had never heard from a human throat. She did not drop the book. She wrenched it toward herself, clutching it hard enough to fold the covers backward, and in the wrench the blade skidded and came up, drawing a second mouth across her stomach. Loops of pale intestine pushed briefly through the wound before slipping back under her trembling hands.

“Read,” Donna hissed through her teeth at Barbara. She reached and smeared her own blood across the opened page with her whole palm and pushed the book against Barbara’s chest. “Read, read, read.” The print stained. The letters drank. For a second Barbara couldn’t see any words at all, only her own handprint on the holy paper, fingers and heel, as if she had been made and remade right there. Then the lines surfaced beneath the red like fish, and she saw: Thou shalt kill, that the gates be opened. She did not blink. She accepted the commission the way a patient accepts a shot. This was not a lie. This was the only sentence she had ever truly understood.

Three men tried to disarm her at once. One got an ear torn in half by the axe’s cheek as it turned. A second caught the back edge across the teeth and spat enamel like salt. The third got his hands on Barbara’s wrists and they danced, panting, cheek to cheek, the axe between them like a hot loaf someone didn’t want to drop.

In the balcony, teens began to throw the smaller hymnals down into the crowd. Each book fell edge-first and opened in midair, pages fluttering, and for a moment the congregation watched print rain and felt soothed, like snow. Then the corners began to cut. People screamed again and tipped their faces up into it with a desperate, stupid hunger.

Old Thomas the usher had found the broken handle. He slid in behind Barbara and jabbed it into the back of her knee. She buckled. The axe lifted, light suddenly, and Donna stepped forward with a noise almost like pleasure and drove her thumbs into Barbara’s eyes. It was methodical. Not a flailing. She pressed until the lids slicked and gave, until her knuckles found the bone of the orbit and seated there. Barbara’s heels drummed. Her mouth opened very wide around the absence of air. Donna pulled her head forward by the hair and kissed her forehead where it was slick and muttered, Thank you, thank you, thank you, as if receiving sacrament.

A boy of twelve — the one who wanted to be a veterinarian before — watched this up close and then turned to the girl beside him and bit a piece out of her shoulder as neat as a heart-shaped bite from an apple. She shrieked and then she laughed and then she bit him back. They fell together into a pew and worked at each other with their hands as if they were making bread.

The air in the church was no longer air. It was wet metal. It was hot coins in a mouth. Shoes squealed. Glass cracked underfoot and kept cracking. Someone pulled the fire alarm, perhaps thinking of order, perhaps hoping to name the noise already happening. The bell did not ring. The tiny red light beside it burned steadily, a bead of blood that never dripped.

Mason did not step down or raise his voice. Instead, he turned a page, and as if on cue, every hand in the room followed, hundreds of pages whispering at once.

“Children,” he read, gentle. “Lay your hands upon the heads of the stubborn and correct them, that order may come. Women, gird your loins with zeal. Men, break bread with iron.”

No one had ever seen those lines in any Bible. No one would ever find them again when this day ended. But in the slow throb of the sanctuary, people saw what they were told to see, and where words ran short the margins filled with little moving letters like ants, and those ants spelled out the rest.

On the back wall, the steel cross tilted another inch. A screw let go with a lonely cry, and the arm sagged. It swung down in a lazy arc and struck a man in a navy blazer under the ear. He fell to his knees in front of the altar as if he had meant to pray, and then his body decided otherwise and made a wet lake around him where his knees slipped and found no traction.

For a minute — a long one, measured in breaths — there was no up or down. Only a circus of limbs. The pews, bolted and obedient for thirty years, gave up and went feral, bucking their riders. A woman tried to open a window with both hands and her hands went through it instead. She turned, delighted, parading her wrists with their new lace bracelets of glass. A man pinned his brother to the hymn-board and stapled the brother’s palm there with a collection plate nail, as if inventorying parts for a future service.

“Look,” someone said. “Look.”

The voice wasn’t loud, but it was the kind of voice the first match makes. It drew eyes. People turned toward the vestibule doors, where sunlight made a perfect square on the floor. The square wasn’t empty. Sunlight from the vestibule stretched across the tiles. In their panic, someone screamed it was a hand, and that was enough for others to see it too. It came from outside. It reached under the doors and through the crack at the bottom and slid along the entryway, long and hungry, and laid itself at the lip of the nave like a dog waiting to be called. Someone giggled. Someone sobbed. Someone said, He is here. Someone else said, He is here, and smiled like a sleepwalker.

Donna stood swaying, the book held out, her stomach mouth opening and closing with each breath, her blood making her sandals talk. She turned in a circle, showing her face to each wall, as if to let the eyes in the corners drink. Barbara found the broken handle again and got to her knees and drove it into Donna’s thigh with both hands. It sank like a stake into damp ground. The sound Donna made then was a baby’s sound, furious and astonished and scandalized. She fell forward onto Barbara and they rolled, two saints in a fresco, their halos red.

A man at the back tried to lead a prayer. He got as far as Father and then remembered that Father was among them and had green and gold eyes, and his mouth closed in gratitude. He put his hand in his wife’s hair and dragged her along the pew like a broom and kissed her forehead too hard. She smiled with all her teeth.

Smoke arrived not from fire but from the candles, which decided to remember what they were for. It grew sweet, like someone boiling sugar too long. People inhaled it and felt a calm so wide they could lay down in it and be covered. From somewhere under the choir loft came a wet, steady thudding, like a boot in a bucket. No one seemed to be making it. No one went to look.

On the pulpit, a fly landed on Mason’s page and rubbed its hands together. He watched it briefly the way a man watches rain, a shared possession of the moment, and then he lowered his eyes again and read softly the line that would put the day into the shape it needed.

“Go now,” he said. “Take the Word that is alive in you. Where the city has slept, wake it.”

A hush moved like a brush across the room. It smoothed hair. It ironed dresses. A handful of heads lifted, faces shining with the rapture of order. Then, as if the bell no one had heard finally rang, bodies began to file out between broken pews and over friends as if stepping over roots in a dark yard. They took up whatever lay to hand because that is what Scripture does when it sits down in a person and decides to steer: a brass candlestick, a broken coat rack, a length of chain left by a workman last spring that no one had noticed until this second and now looked like a rosary for giants.

Barbara lay on her back among the bulletins, breath stringing out in one long thread that might have been the last or the next to last. Donna crawled upright, a supplicant, and put her forehead to Barbara’s forehead, smearing them together until both faces were the same red. “Peace be with you,” she whispered, and when Barbara’s mouth opened to reply, Donna pushed two fingers between her teeth, slow and deliberate, and pressed them against the tongue as if blessing it. Barbara bit down and took the first joint. Donna nodded, eyes bright with tears.

Somebody laughed. Somebody sobbed. Somebody sang the wrong words to a hymn and then sang them again because the wrong words were the right ones today.

The ushers opened the doors without knowing why. Light lay on the floor. Outside, Main Street waited, shy and small at first, then opening its arms. A dog stood on the church steps and wagged its tail once and then tucked it and ran. The sky had gone a color no one could name except to say it looked like a bruise forgetting itself.

In the balcony, the teens looked at one another. One boy with a bad mustache took off his shirt and wrapped it around his fist and punched the stained glass because he wanted to see what it would look like from the inside when the saints broke. It looked like rain made of candy. People clapped. He laughed and bled.

“Remember,” Mason said, and the word folded neatly over the rest. “It is written.”

In a hundred books, the letters shifted like fish again and wrote themselves into new sentences. Those who glanced down saw the page breathe. The longer they looked, the more the text inverted, commandments yawning inside out like pockets. Where the old law forbade the hand, the new law hissed to the hand that it had been wronged and must answer. Where the old way calmed, the new way said a storm is a form of prayer.

At the threshold, a woman stopped and turned back, as if to wave. She looked up at Mason for permission to be what she suddenly knew she was.

He inclined his head.

She stepped into the street with the others.

The steel cross chose that moment to fall.

It came off the wall like a theater light. It swung once and then dropped the rest of the way and hit the front pew, then the next, then the next, eating rows as it went, finally kissing the aisle runner with a spark like a flint. People leapt over it in the flow to the door without breaking stride. One man bent mid-run to touch the hot metal and crossed himself with the hand that came away smoking.

The church emptied itself the way a slaughterhouse releases workers at shift’s end, a cheerful, efficient expansion of bodies into lanes. The last to leave were the ones who had never left first in their lives. They looked dazed with the gift. Outside, the town stretched before them, the cinema with its dead bulbs, the barber pole, the diner. The sun was red and patient. The alleys brimmed with the kind of shade that has plans.

Only then did Mason close the book.

He stroked the cover once, tender as a husband smoothing a skirt, and set it on the pulpit. The page inside cooled, the letters still rearranging in patient, private negotiations only ink understands. He lifted his face.

Smoke curled in the corners, catching the light in shifting shapes that seemed, to terrified eyes, like something watching. Then it thinned and vanished.

Behind him, inside the open book, the verse about the sixth seal lay where he had left it, and if anyone had opened to it then, they might have thought the floor trembled without moving and that the moon was blood at noon and that the sun wore black hair like a veil. But the room was empty now, and the book breathed alone.

The last sound inside the cone-shaped church was not crying or prayer. It was the soft, courteous click of the door falling into its latch when a little wind came from nowhere and pushed it shut.

Outside, Sodom Hills took a breath.

Night would come, and with it, a city that had once slept would now awake the only way it knew how.

Chapter 5 – Bloodbath

That night, the world changed in Sodom Hills. The few who survived would later speak of seeing Pastor Mason standing on the roof of the church, though none could say how he got there—or why the sight made their stomachs turn to ice. Some swore his coat did not move with the wind, as if it were sewn to the air itself, and that his shadow stretched too long for a man’s, spilling across the churchyard like black water creeping into every home. Others claimed his mouth never moved, but they heard his voice anyway, humming an unholy hymn that no one had ever learned and yet somehow knew by heart.

What began in the church did not stay in the church. The words read aloud that morning had taken root. They spread like a sickness, slipping into every Bible, every prayer book, every scrap of scripture left on kitchen tables and nightstands. Letters twisted into shapes no human mind was meant to read. The pages seemed to breathe in the dark. People awoke in the night to find verses glowing faintly, whispering promises that sounded like salvation but tasted like ash. Families turned on one another without warning, their faces serene even as their hands struck out. A mother kissed her sleeping baby, then laid it gently on the rug before lifting the iron poker from the hearth and bringing it down in silence. A farmer gutted his brother with the same knife he’d used on hogs, tears of joy streaming down his cheeks as he chanted lines no scripture had ever held. On the edge of town, a widow walked into her barn and hung herself while humming an unfamiliar hymn, the rope creaking in rhythm with her song. It was not rage. It was worship. And there was no stopping it.

By sunrise, Main Street was an open wound. The air reeked of smoke, sweat, and iron. Bodies lay piled like cordwood in doorways, across hitching posts, and along the dusty road where horse-drawn wagons had once rattled past. The living moved among the dead as though nothing were wrong, their eyes shining with strange ecstasy. A woman in a yellow dress dragged her husband by the ankles through the street, her bare feet leaving smears of red across the dust. Behind her, three children knelt side by side, clawing at each other’s faces as they sang off-key hymns, their little voices cracking on notes that didn’t belong to any church song ever taught. A man stumbled past clutching a Bible so hard the pages tore between his fingers, his lips moving in silent prayer while blood poured from his ears. The butcher’s shop was wide open. Hooks that once held cuts of meat now dangled with human limbs. The town’s horses screamed in the stables, sensing something terrible, kicking until their legs shattered. Rats swarmed into the open street in broad daylight, driven mad by the scent of gore.

The sheriff, Elias Crowder, stumbled out of his office with a Winchester 70 clutched in both hands. His eyes were ringed black from sleeplessness, his uniform dark with other people’s blood. The rifle was long and heavy, a trusted tool in his hands for twenty years, its barrel still warm from the dozen townsfolk he’d already shot trying to force their way inside. They were not strangers. They were neighbors. And he had loved every one of them.

“Back!” he bellowed, his voice breaking as another wave surged forward—shopkeepers, farmhands, the schoolteacher, and the blacksmith, all with their teeth bared and their Bibles held high like relics of some holy war. The preacher’s wife stumbled in front, her white dress soaked red at the hem, her eyes glassy with devotion.

Crowder fired once. A man’s head split open like a melon, spraying the wall behind him. He fired again. A woman dropped mid-hymn, her lips still shaping the words even as she twitched on the ground. Another shot. A young boy flew backward into a window, the glass shattering, his blood running down the frame in long, trembling lines. The rifle’s blasts echoed down Main Street, sharp and cruel, like nails hammered into a coffin. One by one, twelve bodies fell in the dirt, the last collapsing at Crowder’s boots.

For a moment, there was silence. Then the whispering began again, threading through the air like a draft beneath a closed door. It didn’t sound like speech at first—only wind through cracks. But soon the words sharpened, tumbling over one another, a thousand overlapping tongues reciting verses that weren’t verses at all, only commands. The sound rose and broke like a wave, chaotic yet united, as if the entire town had become a living Tower of Babel. It was language turned against itself, not to scatter the people but to bind them together in perfect, ruinous obedience. Crowder felt them crawling into his ears, coiling around his brain like barbed wire. He pressed the barrel under his own jaw. “Forgive me,” he rasped, though he no longer knew to whom he spoke—God, Mason, or the voices in his head. The shot cracked through the street, and the sheriff folded in on himself like an empty coat, his hat rolling away into a puddle of blood and rainwater.

The slaughter rolled on for days, unnoticed by the outside world. Sodom Hills sat alone in the desert, its roads long washed away by sand, its phone lines downed from a storm that no one remembered clearly. No travelers came near, and no signals went out. It was a town locked in its own sealed hell. The sun rose and set over Sodom Hills like a watchful, uncaring eye. Each dawn revealed new horrors. Men carried axes through front yards where laundry still fluttered from the day before. Women drowned their sisters in cattle troughs while chanting backwards scripture in perfect unison. A pair of teenage twins climbed onto the roof of the old drugstore and jumped hand-in-hand, laughing as they hit the ground and did not rise. Children crept through alleys with broken glass and kitchen knives, their laughter thin and high like the sound of wind through reeds.

The church bell rang without hands to pull it, tolling endlessly. Every peal sent another wave of madness through the streets, driving the townsfolk into frenzies so violent the very buildings shook. Houses caught fire, some from lanterns knocked over during fights, others simply because the heat of the collective rage seemed to ignite the wood itself. The smell of rot grew so thick that even the desert coyotes stayed away, crouching on the dunes and whining at a hunger they dared not answer. Buzzards circled overhead in great black spirals, descending only when the screams briefly stopped.

By the second day, the town was unrecognizable. The saloon was a ruin of overturned tables and broken bottles, its piano keys smeared red. The general store had become a slaughterhouse, shelves collapsing beneath the weight of torn bodies. Streets that once held parades were now rivers of blood, flowing sluggishly under the relentless desert sun. It was a vision so grotesque it made a zombie apocalypse look like a child’s fairy tale, a nightmare so pure and unbroken it seemed to mock the very idea of mercy. A preacher’s widow stood in the middle of the square holding her infant aloft like an offering. Around her, a circle of chanting figures knelt, rocking back and forth. When the widow dropped the child into the dust and raised her hands, the others fell upon it like starving animals. She did not flinch. She only sang louder.

Survivors were almost impossible. Almost.

A handful lived because they could not hear the words. The old deaf woman who ran the post office barricaded herself inside with a double-barreled shotgun and a clutch of pigeons, firing through the mail slot at anything that moved. Her world was silent, and so the voices could not reach her. A boy with a throat scar so deep he’d never spoken sat beneath the bridge, his wide eyes watching the town burn. When people stumbled past, he covered his ears anyway, as if even the sight of their lips moving might carry the infection. And a man named Raymond Price, a vagrant who had been blind since childhood, wandered aimlessly through the carnage, guided only by the smell of blood and smoke. He walked among the dead unharmed, never knowing just how close death brushed his shoulder.

These few stumbled away in the final hours, half-dead and senseless, carrying no proof of what had happened except their own haunted faces. When questioned later, they spoke in fragments—shreds of memory that never formed a whole truth.

On the third night, a sandstorm came. The wind screamed through the alleys and tore roofs from houses, scattering ash and pages of scripture across the desert like migrating birds. Flames that had devoured homes in the chaos now smoldered in heaps of charred timber, sending thin columns of black smoke spiraling into the dark sky. Verses written in blackened ink tumbled through the air, sticking to fences and cactus spines, still whispering as they flew. When morning came, Sodom Hills was silent. The streets lay empty except for flies and the hollow shells of buildings, their walls scorched and cracked. The church doors hung wide open, swaying slightly though no breeze stirred. Blood baked black in the heat.

Pastor Mason was gone. No one saw him leave, though a child later claimed she heard singing in the dark—a low, sweet voice that promised the work was only just beginning. Some say they glimpsed a figure walking away from town, his shadow stretching impossibly long across the sand. In the days to come, truckers would pass along the distant highway and remark on the absence of lights where Sodom Hills had once been. They would press the accelerator and drive on, never daring to stop, never knowing what had truly happened there.

Chapter 6 – Amen

Marisol Vega sat alone near the end of the subway car, clutching her tote bag tight against her ribs. It was past midnight, and the Boston train felt like it had been forgotten by the world. The hum of the tracks was the only sound, low and steady, echoing through the long, empty tunnel.

At the last stop, a handful of passengers had gotten off without a word, leaving her by herself. The doors had slid shut with a heavy sigh, and now it was just Marisol and the stale metallic air. She shifted uneasily on the hard bench, her reflection trembling in the dark glass of the window beside her.

The train sped up, plunging deeper into the underground. Outside, the tunnel lights strobed past in a jagged rhythm: light on. light off. light on. light off. The relentless pattern pulled at Marisol’s eyes until they burned. For a split second, she thought she saw a figure standing in the tunnel between flashes, tall and still, watching. She blinked hard, blaming her exhaustion, telling herself she was just tired, just seeing things.

But then the lights inside the car began to flicker too, matching the same uneven pulse. Once. Twice. The car went dark for a heartbeat, then thrummed back to life with a sickly hum.

When the lights returned, she was certain now that she wasn’t alone.

A figure stood at the far end of the car. Tall. Motionless. His outline was black on black, as if light refused to cling to him. A wide, flat sermon hat shaded his face. His coat — or robe — fell all the way to the floor, pooling like a shadow around his feet.

The lights flickered again. The figure was closer.

Marisol’s breath hitched. She slid backward along the bench, knocking her tote bag to the floor. An orange rolled free and thudded softly against the door.

Darkness swallowed the car.

She screamed.

When the lights returned, he stood directly before her. She could smell the cold earth on him, like the air of a crypt. Slowly, his head bent down, and beneath the hat brim she saw his mouth — curved in something that wasn’t a smile.

“My child,” he whispered, his voice smooth and deep, like words spoken from the bottom of a well. “Would you like a Bible?”

He held out a book so worn its leather looked soft as skin. The pages quivered as if they breathed. Marisol didn’t want to touch it. Every nerve in her body screamed to run, to get away, yet her hand moved on its own. Something in her chest — curiosity, terror, or a voice that wasn’t hers — pulled her toward it. She took the Bible, trembling.

The lights went out.

When they came back on, the figure was gone. The train glided silently into the next station. The doors opened with a hiss.

Marisol stumbled out, clutching the book to her chest. She didn’t look back.

Above ground, the city sprawled in restless sleep, unaware that something had arrived to wake it.

END

© 2025 Bernard Kradjian. All rights reserved. This story is the property of its author and may not be reproduced, distributed, or used in any form without prior written permission.